Dear Mr. Elias,

I applaud your recent open letter to Elon Musk.

Just like you, I am the grandchild and great-grandchild of Eastern European Jewish immigrants who led their families “out of the shtetl to a strange land in search of a better life.” Just like you, that background has instilled in me a fervent and passionate belief in the promise of America, and I am greatly alarmed by the existential threat to our democracy posed by Mr. Musk and President Trump.

I also happen to be a professional Jewish genealogist who has spent hundreds if not thousands of hours looking at ship manifests just like the one that you shared in your letter, saying that it shows how immigration officials changed your family’s surname from Eliashevitz to Elias when they arrived in the U.S. in 1904. And I was hoping to set the record straight and show you, through documents, what actually happened.

You may not be aware that the “our name was changed at Ellis Island” myth is a proverbial thorn in every genealogist’s side, a shared family legend that many people defend with an unnerving vigor. It also happens to be a particular fascination of mine, one that I’ve lectured on and researched at great length.

To be clear: It goes without question that countless immigrants changed both their first and last names after arriving in America. But contrary to popular belief, and despite that unforgettable scene in The Godfather, Part 2, immigration officials had no authority or mechanism whatsoever by which to change anyone’s name against their will and there is zero documentary evidence that it ever happened. Including that screenshot.

What that screenshot shows is part of a more complex immigration story. In hopes of promoting greater awareness of the reality of historical immigration practices, and in continuing my Sisyphean quest to try to put the myth to rest, let me explain.

The manifest you shared is from the S.S. Saxonia, which left Liverpool on the 5th of July, 1904 and arrived in Boston on the 14th. (As an aside, you may not know that your family was actually originally set to sail to New York on July 2 of that year aboard the S.S. Carmania, but they, along with more than 40 other passengers, were scrapped from that sailing, perhaps because they arrived in England too late and were reassigned. See line 11 here.)

The most important information in teasing this out, however, is actually off to the right of the snippet of the manifest you shared, in column 15. At the time of his 1904 arrival, your great-grandfather Abraham Elias indicates that this is not his first trip to America. His entry is slightly cryptic, suggesting perhaps that he came five years earlier? Or had been here for five years? Or that he came in 1903? There’s also a notation that someone in the party was an American citizen, but then those words are scratched out.

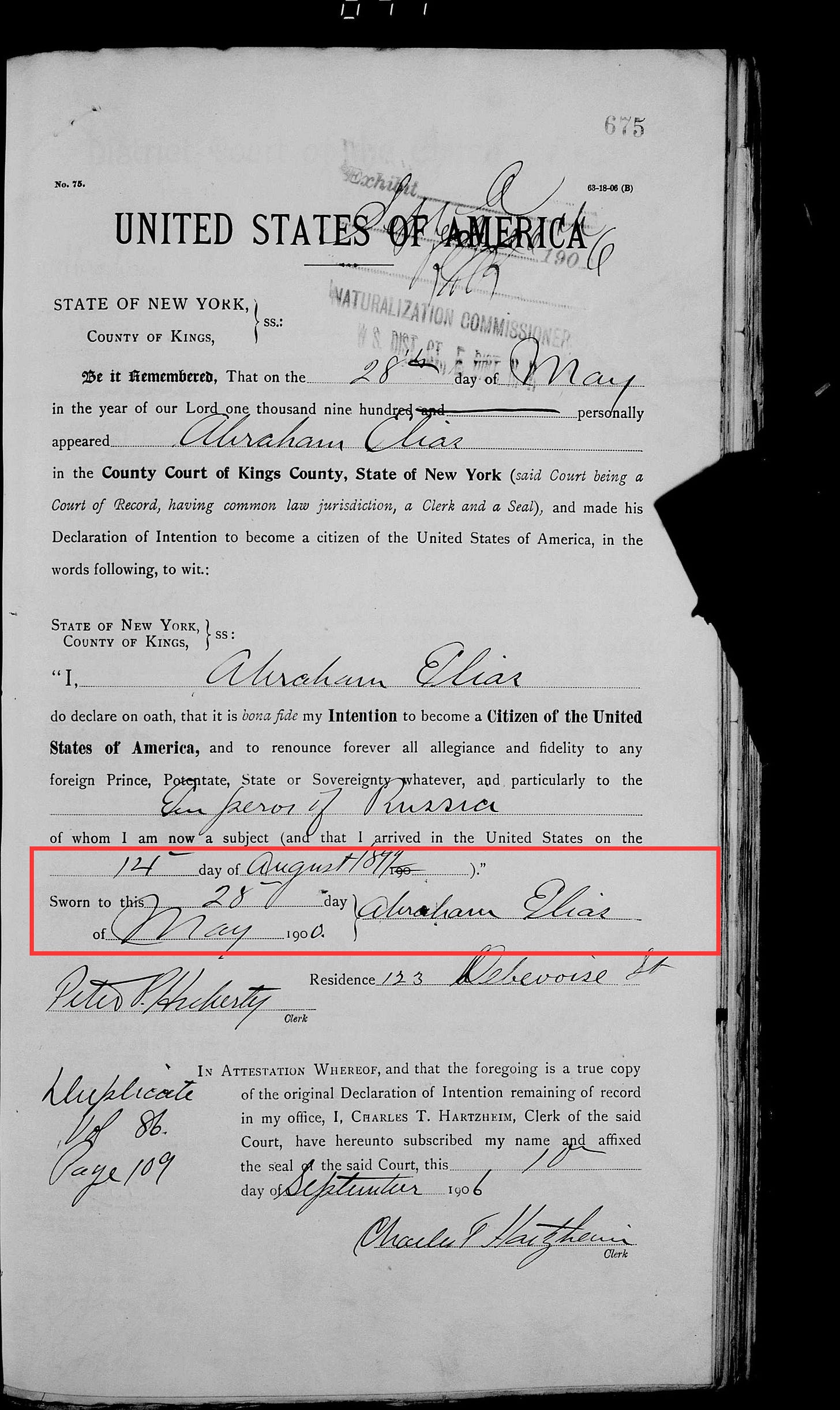

The first clue to clearing this up comes from Abraham Elias’ naturalization petition, finalized in Brooklyn in September of 1906, which indicates that he first arrived in the United States on August 14 of 1899, five years prior to the Boston arrival.

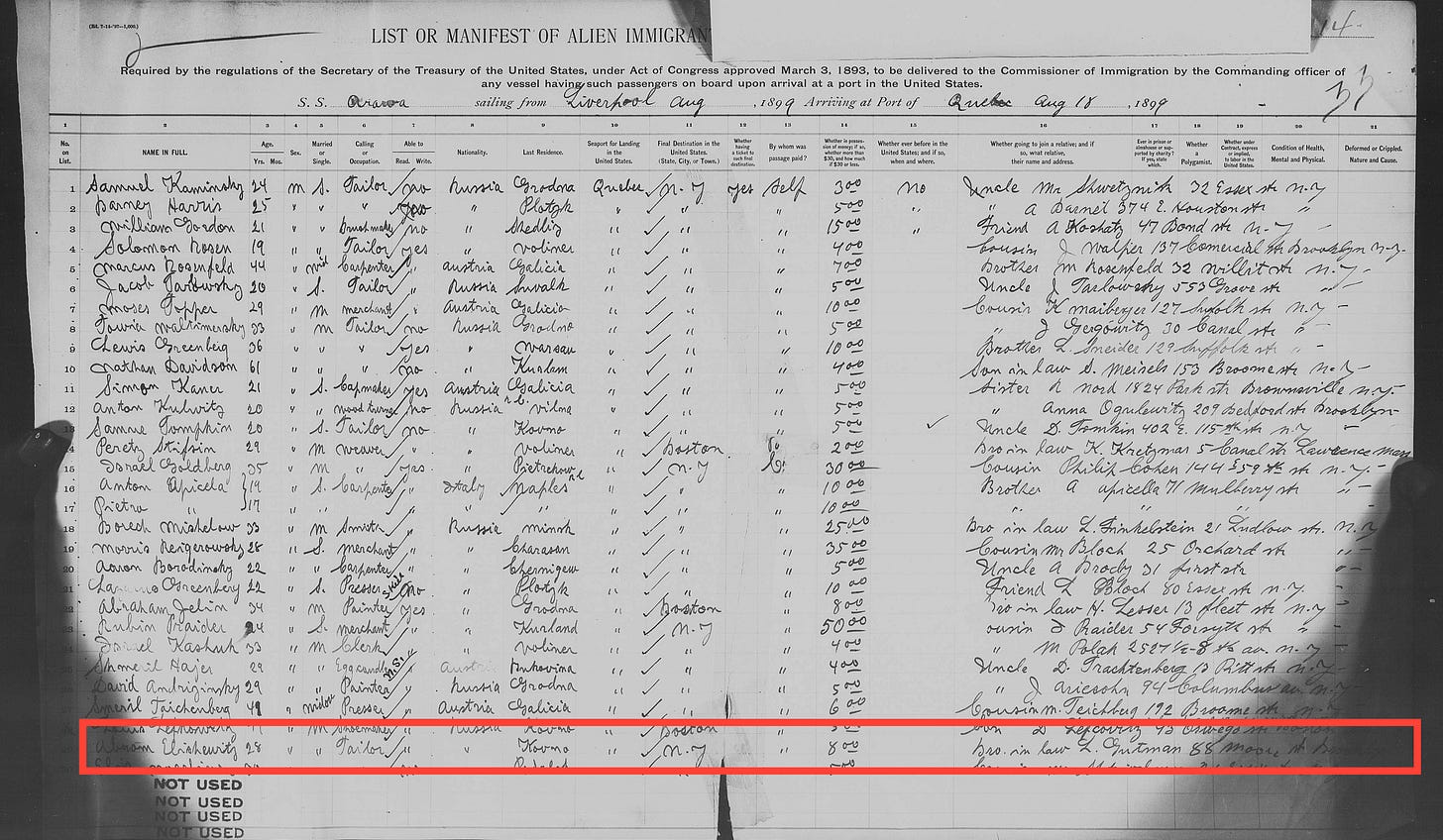

Here is the manifest for that earlier arrival. Abraham “Elishewitz” sailed from Liverpool to Quebec under his original surname with $8 in hand. He lists the same brother-in-law in Brooklyn, “L. Gutman” (aka Louis Goodman,) as his point of contact both here and in 1904.

In May of 1900, just a few months after his initial arrival, your great-grandfather set his naturalization in process by declaring his intent to become a citizen in the U.S. District Court in Brooklyn. And he did so, as countless immigrants did, under a new, shorter name: Abraham Elias. So it’s clear that the name he was already using in New York City in May of 1900 could not have been assigned or chosen for him by immigration officials when he arrived four years later in the summer of 1904: he chose it himself. At the time, there were no legal proceedings necessary to do so, although in later years, formally changing one’s name would be a common occurrence during naturalization proceedings.

At some point after filing this declaration of intent, Abraham Elias went back to Lithuania to pick up his wife and children and then re-entered the U.S. as a family. (Most outbound manifests from the U.S. have not survived, so there is no way to know for sure when he left.)

The markings you see on the 1904 manifest—the original would have allowed us to see the various color pencils used by different annotators—were simply the Boston inspector’s attempt to enforce the law by making sure that the passengers arriving were in fact the people that the shipping company had listed on the manifest. He would have interviewed your great-grandfather, who would have likely indicated that he was already living in the U.S. and had begun naturalization proceedings, hence the possible confusion about whether he was already a citizen. Your great-grandfather may have even had paperwork or identification attesting to the name he had already begun officially using in New York City. The cross out on the manifest (and there are many others on the page) was almost certainly to square those two disparate pieces of information — that the passenger listed as Eliashevitz was now formally going by Elias.

Please continue to fight the good fight and speak out against this terrifying inversion of the values that lured both our ancestors here. You are truly doing them proud.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Mendelsohn

You are so awesome to give Mr. Elias this beautiful gift of insight and knowledge about his ancestry . I am humbled by both of you.

Thank you Jennifer. When I read his letter this comment made me crazy as well. Given that Marc is clearly a thinking person, I am sure he will be more than pleased to learn all of this. Please do share his response.